Talking Early Years: Celebrating 120 Years at LEYF

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

May 13th 2014

Recently, the Chief Inspector for Schools, Sir Michael Wilshaw launched the Annual Report on Early Years 2012-13 with a fairly controversial speech. He threw down the gauntlet to the sector announcing that we were failing our poorest children because we were not teaching them to be school ready. This raised quite a few hackles and many a blog was written challenging his views but at the heart of his challenge lay the question what is teaching and who are the teachers?

There is no doubt, that Sir Michael is not too keen on the PVI sector. Despite Ofsted noting our improvements year on year he remains convinced that we are not as good as schools even for two year olds! He has conveniently ignored the fact that children aged three have been given places in schools for over twelve years and they have not thrived and succeeded as he would like, otherwise he would not be quite so cross about the number of children who are not school ready. The “readiness for school” model is a powerful one brought from the US it promises politicians that all children entering primary school can read and write and conform to normal classroom procedures.

Sir Michael describes school readiness as:

He argued that children as young as two can learn and be taught and inspectors must look for evidence of settings

Well I don’t disagree with Sir Michael. We know from research that the brain sensitivity to language, numeracy, social skills and emotional control all peak before the age of four, which suggests that how we support children in nursery matters greatly for children’s development of key skills and abilities. However, the issue is that children have little time for us to get it wrong and so we cannot make our children the platform for egos or politicking. We therefore need to be clear about our role as teachers and how and what we teach children. The Ofsted report 2012 -13 stated that “Teaching for small children is not blackboards and desks, it is counting bricks when building a tower, learning nursery rhymes and familiar songs, or gently coaching a child to put their own arms into their coat. The most successful early years providers, whoever they are, are focused on helping children to learn.

But to really consider what we mean by teaching we need to answer some other questions:

Let’s begin at the beginning because to understand how best to teach small children we need to understand how they develop and learn; quite different things! Set this in a context that children develop at their own pace so there is no point in teaching them to hold a pencil if they have not developed the physical grasp and coordination skills needed to do so competently. We have to be able to recognise the stages needed to get a child to be able to move from learning how to use his hands and fingers to learning to mark make and eventually learn to write. We also need to understand how the learning is being processed so we can recognise the characteristics of effective learning in the children. Are the children willing to explore and have a go? Can they get involved and concentrate on an activity? Do they have their own ideas and the ability to pursue those ideas? This may be a little toddler finding their favourite posting box and continuing to practice getting the right shapes into the right holes or a brave three year old getting on their scooter over and over until they can keep it upright and eventually scoot with aplomb. We then have to work within a pedagogical framework which articulates the art and science of teaching that we believe will lead a child to learning. That means taking account of every element of what we do from home to nursery and within the wider community. Recently, the UK Education Minister went to Shanghai to admire their success at teaching Maths. However, the parents of Shanghai were much more circumspect about their success noting in an article in the Telegraph that education is cultural and not easily translated. This is worth noting when considering how pedagogy is interpreted through a programme or a curriculum. In the UK the EYFS is the statutory curriculum which shapes the pedagogy .

There are others such as Te Whariki which influenced the LEYF approach because of its integrated care and education central core with a great emphasis on social context and communities and how early years practice can weave thoughtful action into social justice. The pedagogical principles are designed so as to ensure services that are individually, developmentally, educationally culturally and locally appropriate. A common framework also helps parents understand an approach and how we teach children. It is more likely to ensure a stronger home learning environment by more explicit information sharing about what we do in nursery.

The LEYF approach automatically encompasses the learning requirements of the EYFS but is very influenced by theories of Froebel, Pestalozzi, Vygotsky, Bruner McMillan, Montessori, Gardner, Putnam and the emerging research on neuroscience. So for example one aspect of Montessori’s influence is evident in how we support children’s Independence by teaching them to dress themselves, help tidy up, use real tools and understand their role in the local neighbourhood. Bruner comes alive in the way we give the children opportunities to explore their communities and connect with their sense of place, McMillan influenced our urban outdoors approach while Vygostky guides our emphasis on social interaction, conversations and the importance of understanding their role within the nursery.

When asked how children learn we will more than likely say “ through play”. This simple statement is often misunderstood. Play is a complex process and necessary for children to become adults. Play-based, as opposed to “drill-and-practice”, curricula designed with the developmental needs of children in mind can be more effective in fostering the development of academic and attention skills in ways that are engaging and fun (Brooks-Gunn, 2007). However, in a healthy nursery, play does not mean “anything goes” but neither be so tightly structured that children are denied opportunities to learn through their own initiative and exploration. Faster is not better so children need time to repeat and practise and staff need to be sensitive in how much the repetition is planned. For example a child needs to hear a word 20 times before it become part of their vocabulary.

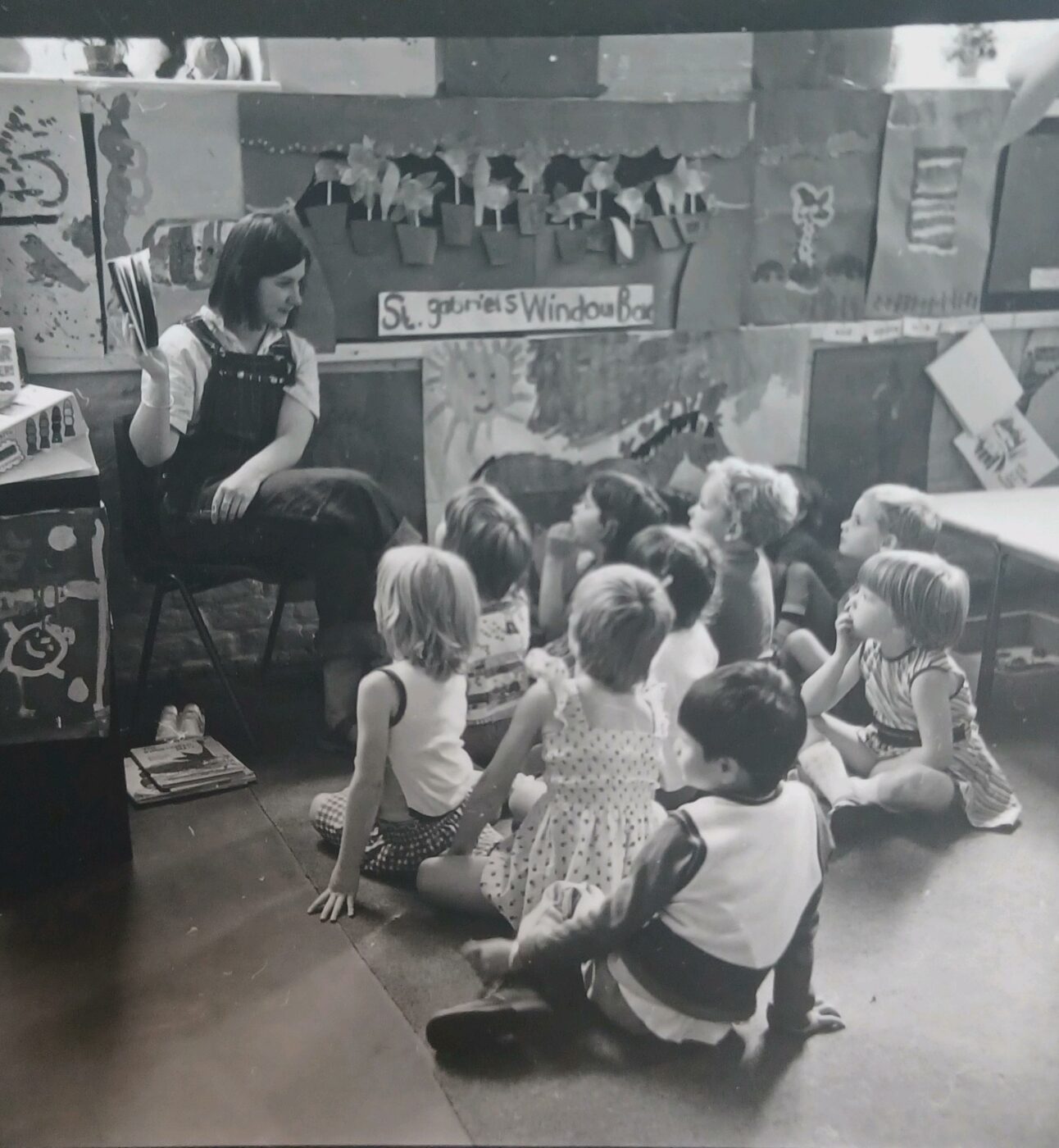

In practice teaching in the Early Years means adults who can weave together child led first hand, sensory and fun experiences through play in a suitable environment balanced with adult initiated planned activities where we can challenge, extend and scaffold the children and their interests in a way that takes account their learning styles and their developmental stages. Children learn from adults who create a space where together they float on a sea of rich conversations, positive modelling, repetition, extension and corroboration and where adults use a range of carefully selected teaching strategies including listening, observing, modelling, questioning, negotiating, demonstrating, extending and acknowledging and valuing children learning.

I’d be interested to hear your views – What is teaching and who are the teachers in Early Years?

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

The other night I was watching my new late-night Netflix addiction, How to Get Away With Murder. I have reached Series 5 where the main protagonist, Annaliese Keating is…

We all know that the Tiger comes to Tea but we have never had a Duchess come to Breakfast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6hzbLzcprE The Duchess of Cambridge lightened up our…