Talking Early Years: Celebrating 120 Years at LEYF

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

July 15th 2014

Last week I spoke at the UK National Literacy Conference. My role was to share how we support children to become literate in LEYF nurseries. This is very important at LEYF because our model is designed to extend children’s cultural capital by increasing and enriching their language and literacy.

We believe that communication is the foundation for language and literacy. Children are sensitive and enthusiastic communicators from birth and have an instinctive ability for tuning into non-verbal communications, spoken language and using them for their own purposes. At LEYF we use the mantra ‘two words together at two, 1000 words by three and fluent by four’. That is an expectation for all children whether or not they are acquiring two or three languages simultaneously, as is the case for 80% of all LEYF children. Being able to speak more than one language is a great gift and one we nurture and support across the organisation.

Sadly in London currently, despite the huge improvements in schools, one in four children leave primary school unable to read or write properly. We therefore have to play an early part in eliminating illiteracy across the city. The research by Sylva et al (2008) makes clear that the effect of attending a high-quality preschool on a child’s literacy and numeracy at age 11 can equal or surpass that of other factors, including primary school quality and early developmental problems. Last year, the review of the two year old pilot confirmed the importance of high quality settings for disadvantaged children’s language (as defined by IDACI scores). This assessment came from ITERS and British Ability Vocabulary System (BAS) data and suggested the improvement could be as much as moving a child from the 34th centile to the 46th centile. Pretty amazing in my book.

Better still, the follow up by Maisey in 2013 using an evaluation of the old profile, found that language and creativity improved and was sustained once moving into school. Is it any wonder we remain depressed by a Government failing to acknowledge this? Why penny-pinch and look for reasons to ignore and downgrade early years instead of funding the quality that will make this huge difference to our society? If they won’t listen to us, maybe with an election looming the words of Kofi Annan might jog a sensible response:

“literacy unlocks the door to learning throughout life, is essential to development and health, and opens the way for democratic participation, active participation and active citizenship.”

“Good literacy floats on a sea of talk” says James Britton, and so say many of us. To be a confident reader you need to be a confident talker. Nurseries need to be a hive of conversations with children and staff playing, talking and listening to each other. Teaching the children how to converse, interject, listen and respond is critical. We also need to use routine and resources to extend and embed literacy and language. At LEYF we use Makaton and visual timetables to help with this.

Having fun with stories, poetry, songs and drama is key and we have reintroduced Vivien Gussein Paley helicopter time where children and staff use drama to build up and record children’s stories.

“Stories that lead to doing things are all the more attractive to children, who are active rather than passive creatures. Myths and fairy tales provide an unusually abundant choice of things to do… they can be re-created by children not only in words but in drama, in mime, in dance and in painting.”

– The ordinary and the Fabulous, an Introduction to Myths, Cook 1969

What a shared pleasure we have by creating a love of stories using funny, beautiful, nonsensical, and sensual words as well as interesting, sensitive and creative storytelling. Lovely shared reading time when the child with a friend or with an adult just wallows in a good story.

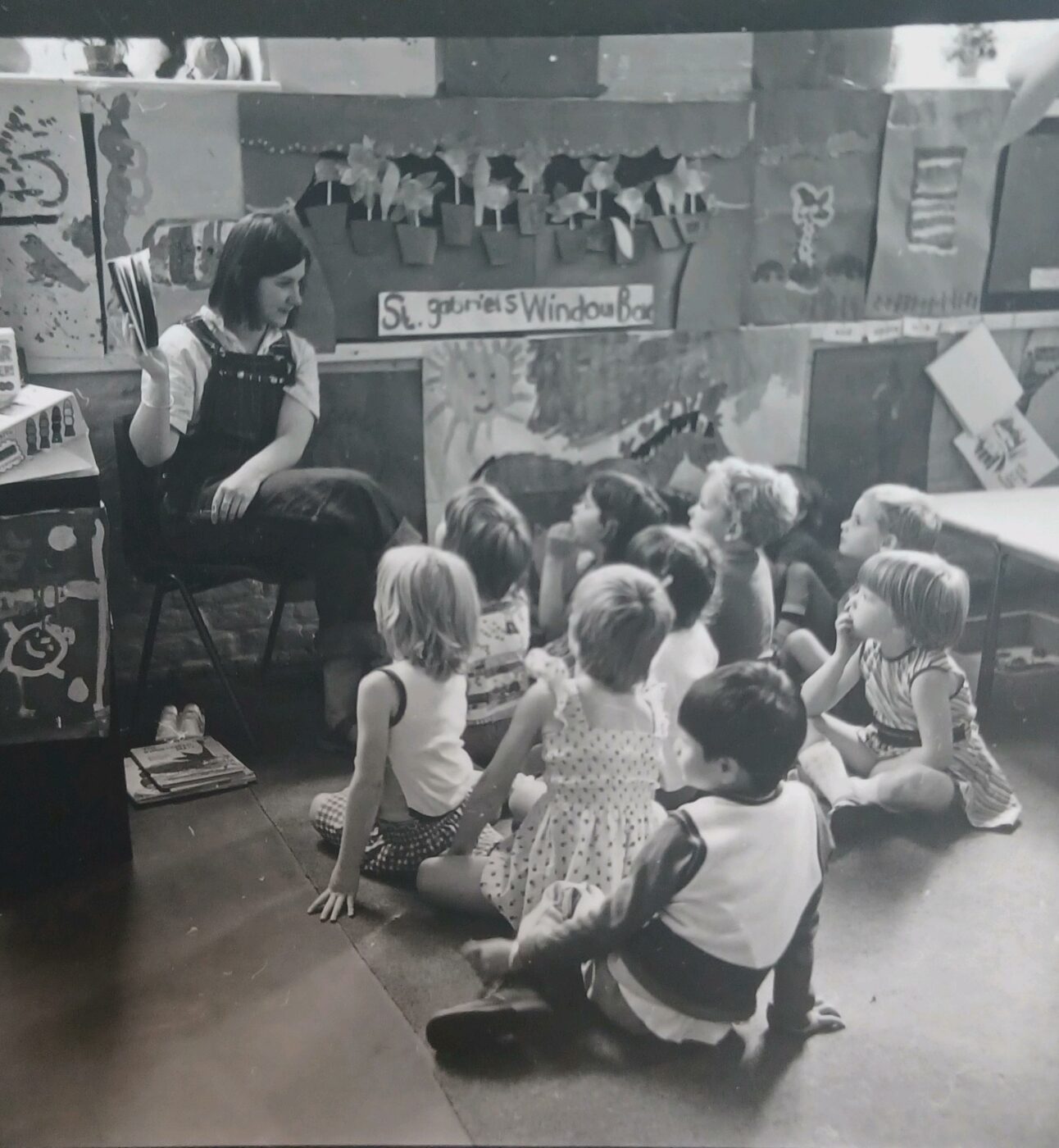

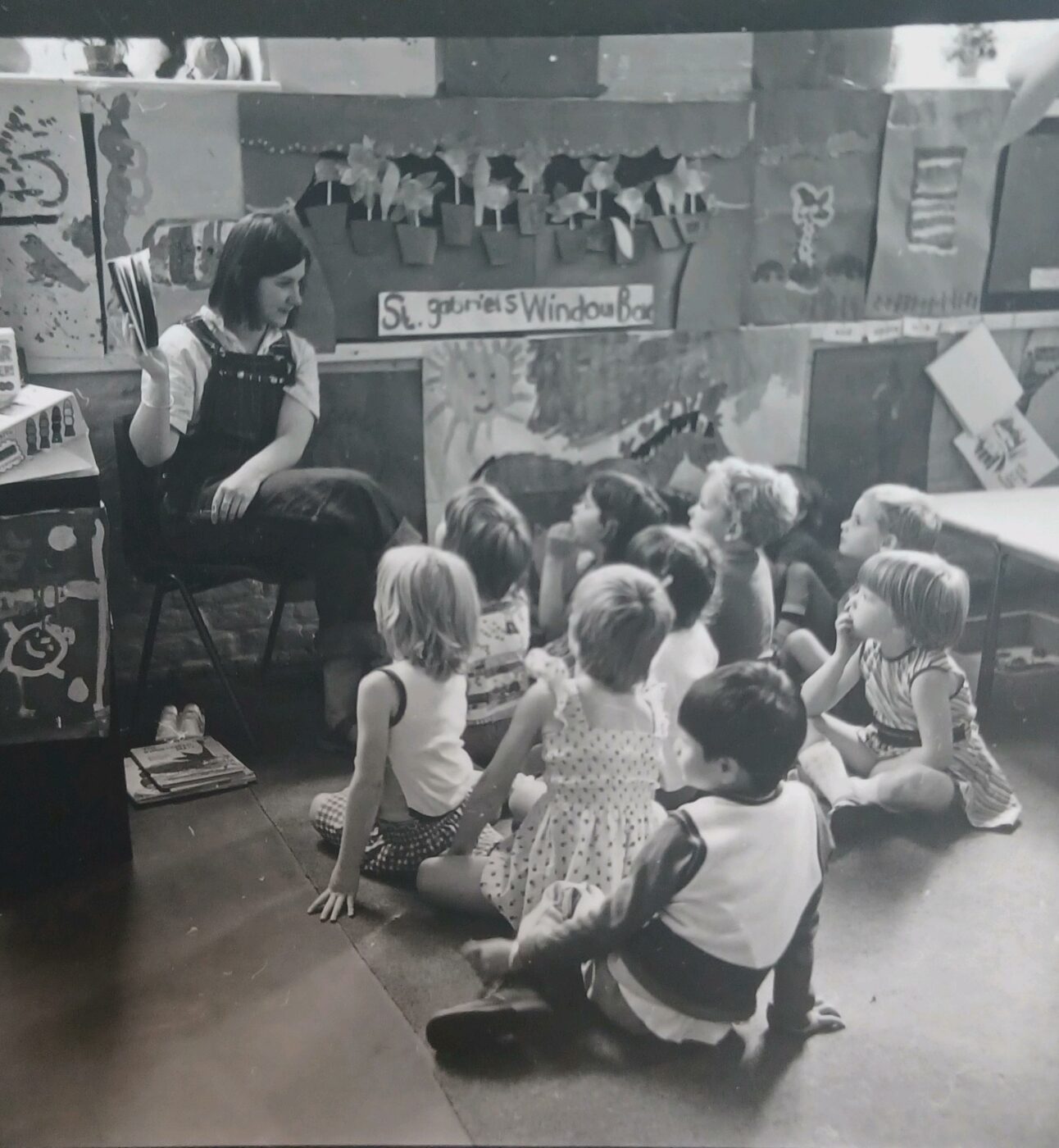

When reading with children in a group or when using reading to extend literacy and language we have introduced the dialogic reading techniques. Dialogic story reading develops grammar, listening comprehension, and the ability to form an argument and to elaborate and use expressive language skills. It also helps children use more words, speak in longer sentences and score higher on vocabulary tests (Whitehurst and Lonigan, 1998) (NELP, 2008).

“We now know for certain that children who handle books confidently before they go to school, and have enjoyed being read to, are those who learn to read in school with the most success.”

– Margaret Meek

Reading stories aloud to children is one of the most highly recommended activities for supporting their language and literacy development and by using dialogic reading, the adult helps the child become a confident user of books, able to tell the story and talk about it and make wider links. That way the adult becomes the listener, the questioner and the audience for the child (Whitehurst, 2002).

Dialogic reading, simple steps:

Of course, in order to become a reader, children need to understand that written language conveys messages. Every nursery must have a very clear approach to mark making so our children can become emergent readers and writers and be the bloggers of the future. So as well as sharing our approach to supporting children to read and write I tackled the issue of phonics.

This is one example of how politicians get a bee in their bonnet about one solution and want to apply it everywhere. Phonics is one of those buzzing bees and certain politicians would try and solve word peace with phonics. In fact, I was invited to a TV channel news programme to talk about “failing education” and a politician was also on the panel. I said flippantly “I suppose you think phonics is the cure for educational failure” and he nodded earnestly and said “yes I do”!

The LEYF approach to phonics is best summed up as phonological awareness where children begin to understand the sounds of words through happy, noisy chanting and singing, nursery rhymes and word play.

Phonics is a strange subject for people to get emotional about, but it gets people going. It was the part of my speech that generated most conversation afterwards. There are arguments for and against and academics argue that it could be too reductionist as a reading approach and lead to disaffected readers. Of course, children need to do more than decode print and make sounds to match the marks on the page, blend them together and pronounce a word to become a reader. Reading involves significantly more than knowing the sound/symbol relationship. They have to understand context, references and nuance.

Children learn to read when they are engaged and enthused and that starts by getting them to fall in love with books. So we have chosen books with the help of the Letterbox Library that are made up of rhyme, rhythm and rhymes that play with words, alliteration and repetition. A great collection including favourites from Annie Kubler, Nick Sharrat, Jill Murphy, Eric Carle, Giles Andreae, Julia Donaldson, Michael Rosen or my particular favourite at the minute, The Worst Princess. This will soon be rolled out to all our parents.

So to those politicians, who like a simple answer, let me share a few thoughts. Learning a language, both spoken and written, is culturally framed before and outside of nursery and school so let’s engage with the families and create a bridge between the home experiences and new learning. Research (Kassow 2006) tells us that home literacy behaviours include activities such as observing parents reading (books, magazines, newspapers, bills), writing (shopping lists, menu planning, letters), visiting the library and engaging in shared book reading with parents. Talking counts especially when you note what Childers and Tomasello (2002) told us: a child needs to hear a word 20 times before it becomes a part of their vocabulary. Children who are read to three times per week or more do much better in later development than children who are read to less than three times per week. They need to read the books together over three to five days. This is what we need to focus on. So more Bookstart and other ways of exploring the home link, less focus on one element of reading. In the end the shared aim is for everyone to enjoy reading together, become shared storytellers and build a positive shared attitude to reading.

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

The other night I was watching my new late-night Netflix addiction, How to Get Away With Murder. I have reached Series 5 where the main protagonist, Annaliese Keating is…

We all know that the Tiger comes to Tea but we have never had a Duchess come to Breakfast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6hzbLzcprE The Duchess of Cambridge lightened up our…