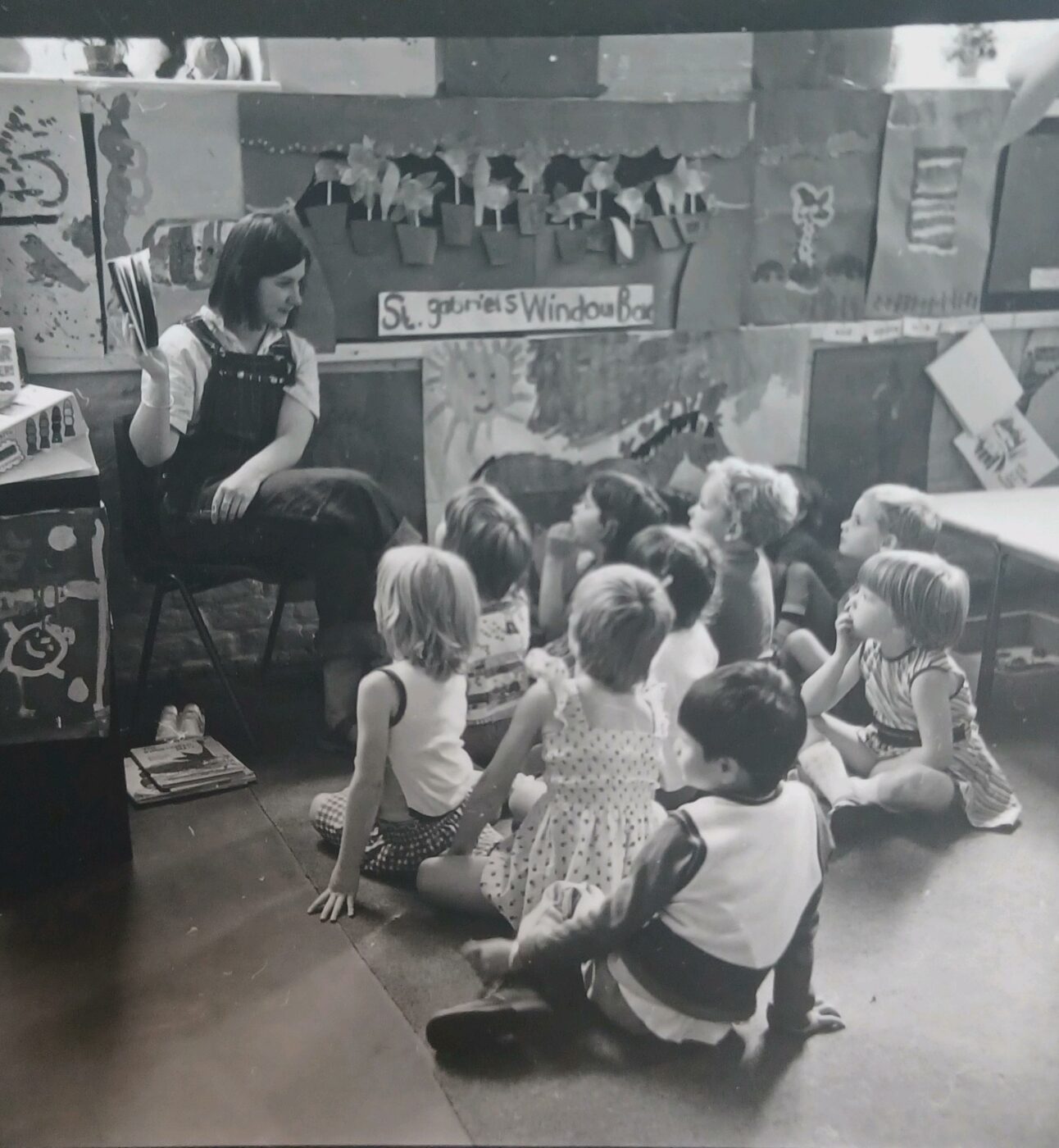

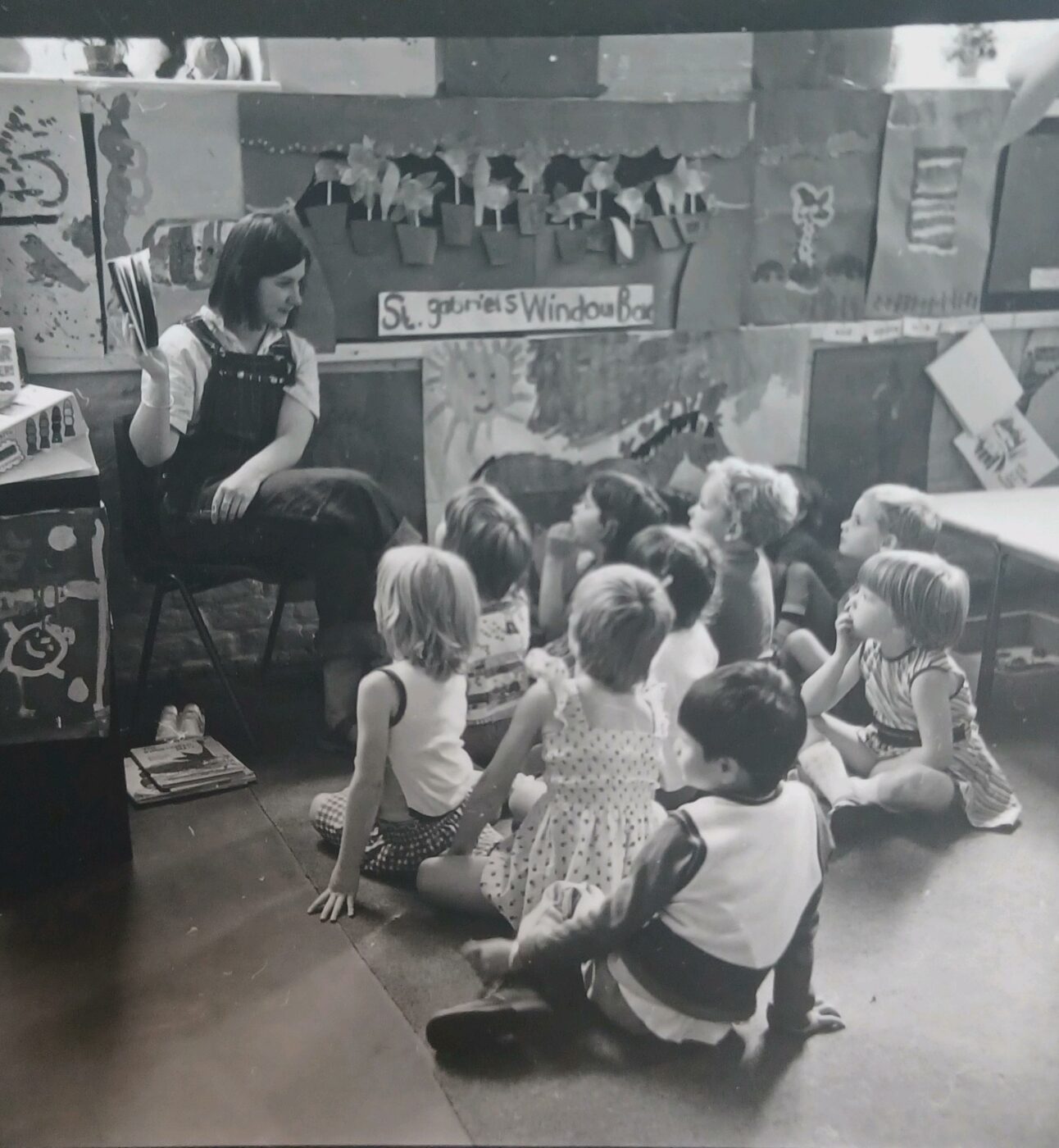

Talking Early Years: Celebrating 120 Years at LEYF

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

May 3rd 2012

Two ever-popular and increasingly connected topics of debate, child poverty and social mobility have been high on my own agenda this week. Starting on Monday with a lunchtime debate hosted by Policy Exchange, entitled Towards a Better Child Poverty Target. Here an eminent panel of five, including Frank Field MP argued that the targets set to reduce child poverty were unhelpful. Kicking off the debate, Frank provoked the audience with real life examples of child poverty, and a heartfelt plea in support of all those children who are subject to the casual cruelty of ignorant adults. He concluded by asking Mr Cameron to read his report. (Leaving me to wonder how he knew the Prime Minister had not already done so.)

Next up was a representative of the End Child Poverty Campaign, arguing that we should have targets, not only since poverty damages children’s life chances, but since lower income equates with poor educational attainment which in turn leads to poverty. The Director of the Policy Exchange then suggested the measurement of 60% of the median income was somewhat arbitrary and needed to include relative poverty. He challenged how measurements can be deceiving, and statistically getting someone out of poverty may still leave them poor. He challenged the audience by saying that we did not really understand what caused poverty. For example we always assume that unemployment leads to poverty, whilst research from the Institute of Fiscal Studies was unable to link higher employment with a reduction in poverty. Much was made about poverty of the ‘in work’ population (something we often see at LEYF), itself mitigated to some degree by Child Tax Credits; although now a situation clearly challenged by the Chancellor’s budget decision to reduce access to tax credits.

The editor of the Spectator, Fraser Nelson told us that poverty was not sexy and it certainly did not sell newspapers. Apparently, the public simply don’t get the notion of poverty. They don’t see people starving and so are unable to understand the issue; it is in effect a hidden problem. And it seemed no-one had a solution that might change this.

Finally, the debate began to focus on Early Years and the importance of early intervention. Reference was made to the negative impact of maternal deprivation, along with persistent and severe poverty on children’s development and their resulting low attainment, which in turn leads to lower levels of lifetime success.

The same subject was also raised on Tuesday by the APPG on social mobility, whose report looks at the causes of social mobility and what that means for policy makers. Called 7 Key Truths about Social Mobility, this must-read report tells us that in fact we don’t yet fully understand social mobility. It points out that to have true social mobility, some people have to go up and others go down, and goes on to say that social mobility is stuck in the UK; apparently those of us in my age bracket (guess) have seen greater social mobility than our children. It may be that education is the factor differentiating us from our parents, and so is the most effective lever. Nowadays it seems less effective, as so many young people already have a more equitable start. Either way, the seven truths they found were:

Unsurprisingly, none of this is new to me (or I’m sure most of the readers of this blog). In fact, it’s this very understanding that drove me into the arms of cultural capital research which now permeates much of what we do at LEYF, from both an economic and social perspective. It’s summed up in this equally relevant interim report on Sure Start delivery in 2011/12, produced by the APPG for SureStart. It states that

All those involved in providing early education and childcare services should encourage a broad social mix of children to attend high quality childcare services. They should address any barriers that may hinder participation by vulnerable children, such as geographical access, the cost of transport or a sense of discrimination and stigma.

It immediately brings to mind a recent example of cultural capital at work in our Holcroft Community Nursery. In this case, two children were on a holiday placement having recently left for school. Chatting away happily – and blissfully ignoring the adults seated nearby who only tuned in ‘mid flow’ – the conversation went something like this…

Child #1: “Key Managers?? Yes, Sherrine is my Key Manager.”

Child #2: “What does Key Manager mean?”

Child #1: “It’s your friend to tell you what to do, make sure you’re OK. Like the leader they are always the oldest.”

Child #2: “Oh, OK.”

I could draw a number of conclusions from this, but the most powerful for me was the sense of connection and confidence those children had about how things work. Cultural capital is the means of firstly helping children gain knowledge and then continue to develop and create it by understanding the system, before sharing this knowledge and making new connections. This is what helps children get on, and it’s when children struggle to understand the system that they are truly disadvantaged.

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

We have been raising the issues of childcare funding for over 10 years. It has been so long, I am amazed at how patient I’ve remained – and…

In the beginning of 2022 So here we are. The final blog of 2022. And hey, we’ve managed to get through what has been a year of discontent and foolishness.